High School Graduate Trends — A Glimpse of the Future Before COVID-19 Intervened

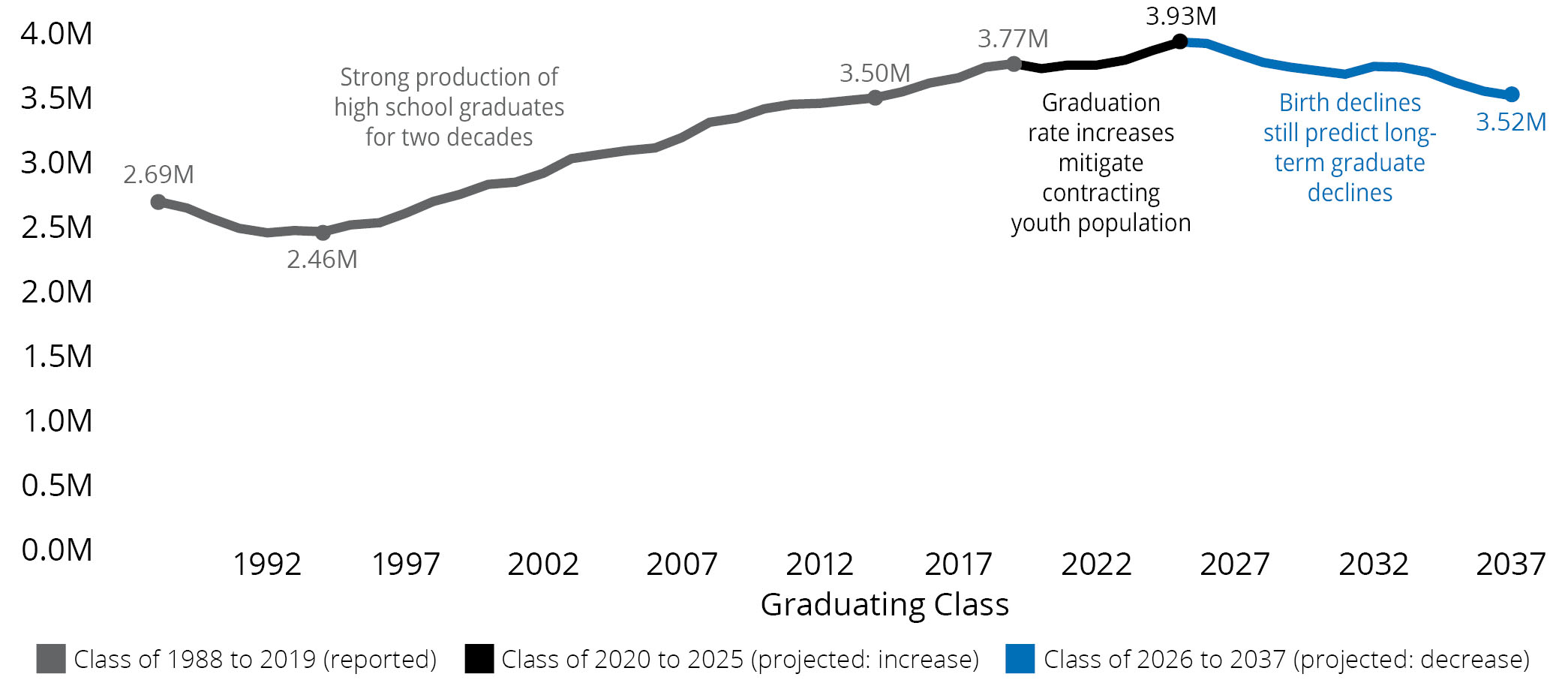

Understanding the pipeline of high school graduates is crucial for a range of policymaking, economic development, and higher education planning needs across the country. WICHE’s 10th edition of Knocking at the College Door projects the numbers of high school graduates disaggregated by public and private schools and race and ethnicity out to 2037. The new projections show – generally speaking and with caveats about state and regional variation – slightly increased numbers compared to previous projections (now hitting a peak of just under four million graduates in 2025 compared to projections in the previous edition of just under 3.6 million). But the projections still follow the previously projected trend line with a decline beginning in 2026 and ending at around 3.5 million graduates in 2037. This decline traces its origins back to the steep drop in births that began with the Great Recession.

While the projections show a slightly improving picture for the number of high school graduates – due in great part to increases in high school graduation rates – they come with an enormous asterisk. Due to data availability, the numbers presented here represent actual enrollments and graduates from public schools through the Class of 2019, and from private schools through the Class of 2017, with the years from 2020 and forward being fully projected. Therefore, due to the timing and lack of available data, these projections do not capture any of the impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic, which is likely to have substantial long-term impacts on the education pipeline.

New Projections Fill a Data Gap about What Graduation Improvements Have Meant for the Number of High School Graduates Over the Last Decade

These updated projections depict the changing student landscape, including how graduation rate improvements have increased the number of projected graduates between 2010 and 2019 and overall growing enrollments of public and private middle and high school students through 2025. The updated projections fill a growing gap in the data that are available for education planning and that are crucial for efforts to improve racial equity throughout the educational system (the annual number of U.S. public high school graduates, by state and race/ethnicity, were previously available through the U.S. Department of Education publicly available datasets or Digest of Education Statistics, but have not been available from these sources for the Class of 2014 to 2019).[1]

The projections continue to depict the increasing diversification of high school graduates that has been a steady feature of these projections for years. The updated data show how historically underserved students – including Black, Hispanic, and other racial/ethnic groups – make up an increasing share of the total graduate population. In particular, Hispanic students and those identified as multiracial are projected to make up a growing proportion of graduates. Higher education does not need more arguments for addressing the glaring inequities among how it serves students of color (other than it being a clear moral imperative), but these data underscore the fact that the traditional-aged student body of the future will continue to have a larger proportion of students from diverse backgrounds.

Trends Predicted by Pre-COVID-19 Conditions Can Be a Benchmark for What Comes Next

These projections indicate future numbers of high school graduates as if the country were proceeding from the gains in graduation rates (as well as grade-to-grade progression rates) made before COVID-19 and the ensuing economic disruptions that have emerged. Of course — that is not the current reality. There is high likelihood that COVID-19 will materially impact the eventual number of graduates.

This information will be crucial for understanding the impact of COVID-19 on enrollments and graduations. Historically, the first few years of our projections are extremely accurate. If we see – as many expect – deviations from the projected numbers, it would be safe to link these changes to COVID-19. Importantly, the data by race and ethnicity of high school graduates could help discern whether COVID-19 appears to be impacting student progress to graduation disparately.

Longer-Term Less-Than-Rosy Trends Could Be Better or Worse Depending on COVID-19 Recovery

The fundamental value of these projections persists despite anticipated COVID-19 impacts. The projections continue to illustrate diversification of U.S. high school graduates that has developed and accelerated over the years. And, more recently, the projections show the impact of decreasing U.S. birth rates – particularly during the Great Recession – which will result in a decline in high school graduates and young workers starting in 2026.

These fundamental demographic changes are here to stay, but they can change around the margins. Comparing the 2016 edition of WICHE’s projections with these data show a 10 percent increase in the size of the peak in 2025. The key question is how much (if at all) COVID-19 will adjust these trends and – if there are big negative impacts on retention, progression, and completion in the K-12 system – how long it takes for our education system to recover. The already less-than-rosy picture for the longer-term number of high school graduates will be worse (or better), depending on how students and schools fare through these challenging times.[2]

Going forward, the “birth dearth” starting in 2008 that predicts a downturn in graduates beyond 2025 does not necessarily predict a reduction in sheer numbers across all ethnic and racial subpopulations. Continued graduation improvements could yield more graduates than predicted (a “thrive” scenario). Stable graduation rates would at least fulfill what is predicted (the “persist” scenario). And, if COVID-19 negatively impacts students — particularly underserved populations and low-income students — the already somewhat sobering projections for high school graduates from 2020 to 2037 could be hastened and amplified (a “deteriorate” scenario). Under this scenario, as a society, we could see an increase in the number of adults without a high school diploma.

The projections come as most states are working to reach ambitious attainment goals. The data show (consistent with previous editions) that states cannot simply rely on an ever-growing pipeline of high school graduates to fuel growth in their attainment rates. As has been written at length elsewhere, making improvements in the graduation and retention of students and better serving adults are keys to improved attainment rates as the growth in traditional-aged students declines from its peak.

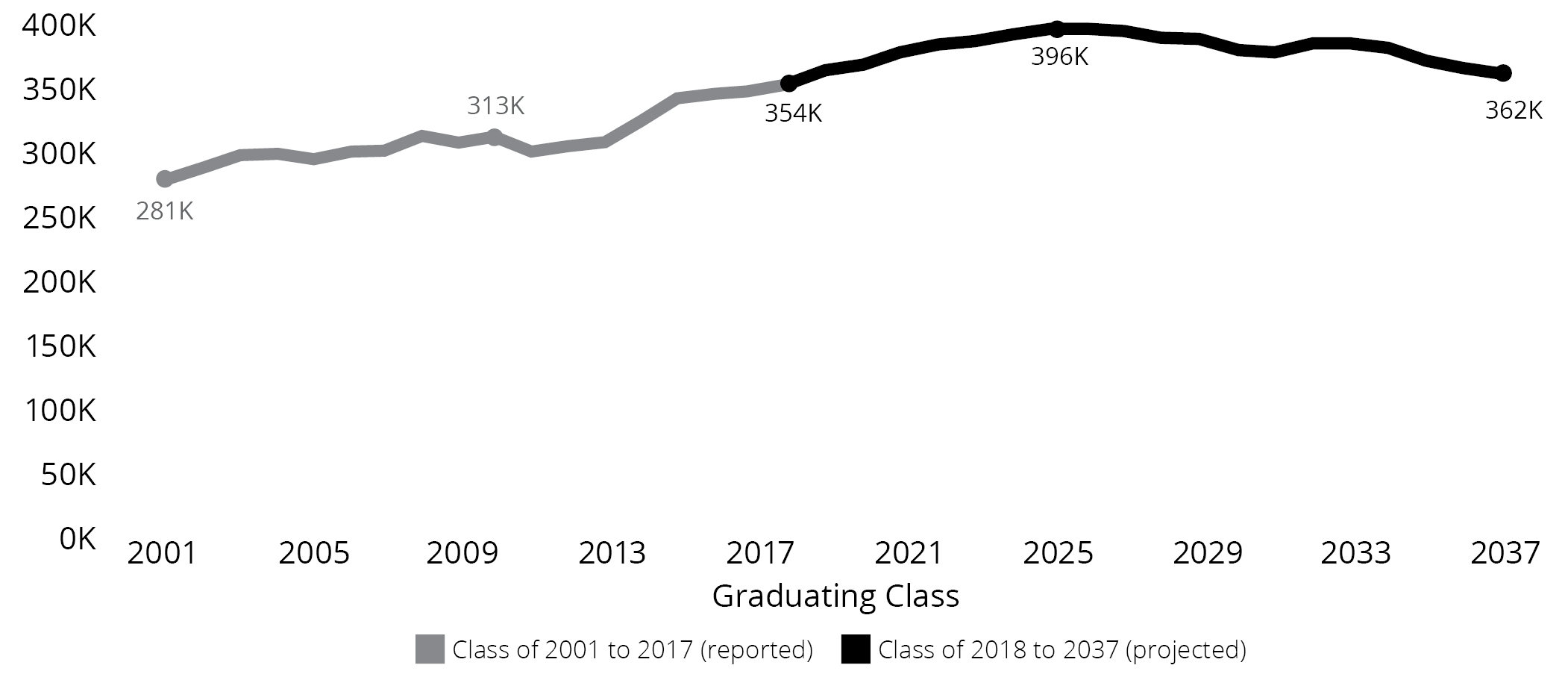

Number of U.S. High School Graduates Projected to Climb Slightly for Five Years

Figure 1 shows U.S. total annual high school graduates from the early 1990s through the Class of 2019, then continuing with this 10th edition projections through the Class of 2037. (This is the year through which WICHE can produce projections based on available data about recent U.S. births). According to the data WICHE collected from states, the U.S. produced 3.8 million high school graduates by the Class of 2019.[3] U.S. high school graduates are projected to peak in number at nearly 4 million (3.9 million) with the Class of 2025, potentially achieving 4 percent increase from current numbers.

Figure 1. Slowing Growth in Number of U.S. High School Graduates, then Decline (U.S. Total High School Graduates)

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. See Technical Appendix for detailed sources of data through the Class of 2019; WICHE projections, Class of 2020 through 2037. (View states or regions)

Fewer High School Graduates are Predicted Past 2025 Due to Smaller Elementary School and Birth Cohorts

As seen from the national and state views below, after 2025, the number of potential high school graduates is impacted by the birth dearth that followed the Great Recession. The U.S. should expect successively fewer graduates in virtually every graduating class between 2026 and 2037, as predicted by smaller elementary school and birth cohorts since 2007. The U.S. high school graduating Class of 2037 is projected to be about the same in number as the Class of 2014 (3.5 million). This longer-term trend is predicted by consistent annual declines in U.S. annual births, about 1 percent annually, since the nation’s high number of 4.3 million births in 2007.[4] Specifically, there were 3.7 million U.S. births in 2019, 13 percent fewer babies born than in 2007. This was the lowest number of annual births since 1988. Correspondingly, an almost 11 percent decline of graduates is predicted between the Classes of 2025 and 2037.

These smaller birth cohorts are moving through elementary schools now. In fact, the predicted smaller high school graduating classes of 2026 through 2030 are reflective of declining student numbers now progressing through elementary schools. The further declines past 2030 relate to the successively smaller birth cohorts from 2012 to 2019, as birth rates did not recover following the Great Recession.[5] Sections below describe the predicted trends among public high school graduates by race/ethnicity, but it is instructive to look here at the birth trends by race/ethnicity below the overall total. The birth decreases have occurred for all of the reported races/ethnicities, except Asian/Pacific Islander (Table 1).

Table 1. Annual Births by Mother’s Race/Ethnicity (U.S., Thousands)

| Total | Hispanic | White | Asian/ Pacific Islander |

Black | American Indian/ Alaska Native |

|

| 1990 | 4,158 | 604 | 2,705 | 138 | 674 | 38 |

| 1995 | 3,900 | 680 | 2,435 | 157 | 593 | 35 |

| 2000 | 4,059 | 816 | 2,400 | 196 | 607 | 39 |

| 2005 | 4,138 | 986 | 2,303 | 221 | 587 | 41 |

| 2010 | 3,999 | 945 | 2,180 | 238 | 596 | 41 |

| 2015 | 3,978 | 924 | 2,152 | 271 | 594 | 37 |

| 2018 | 3,792 | 886 | 2,017 | 270 | 584 | 34 |

| 2019 | 3,746 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Source: WICHE analysis of natality data from U.S. Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics. Showing selected years. The latest year available is 2018 for births by race and ethnicity, 2019 for totals.

Annual birth declines have been occurring with White non-Hispanics since 1991, and these smaller cohorts were evident by the graduating Class of 2011. The birth declines since the Great Recession deepened the trend: there were already 14 percent fewer White non-Hispanic births in 2007 than in 1990 (0.8 percent average annual declines); then a further 14 percent fewer White non-Hispanic births in 2018 than 2007 (1.2 percent average annual declines).

Annual Hispanic births overtook Black non-Hispanic births in 1993, to become the second largest racial/ethnic category for births: 667,000 Hispanic and 649,000 Black births in 1993, compared to 2.5 million White non-Hispanic births. Then, between 1993 and 2007, annual Hispanic births almost doubled (to 1.06 million). And by that point, there was almost one Hispanic birth (1.06 million) to every two White non-Hispanic births (2.33 million), and almost two Hispanic births for every one Black non-Hispanic birth (632,000). However, after 2007, the greatest decreases in births accrued with Hispanic mothers – with 17 percent fewer Hispanic births in 2018 than 2007 (1.5 percent average annual decline). American Indian/Alaska Native non-Hispanic births also show a large rate of decline, with 22 percent fewer American Indian/Alaska Native non-Hispanic births in 2018 than 2007 (2 percent average annual decline).[6] Black births declined 0.7 percent average annually over this same timeframe. On the other hand, Asian/Pacific Islander births have increased in almost every year since 2007, to the pace of 0.9 percent average annual increase.[7]

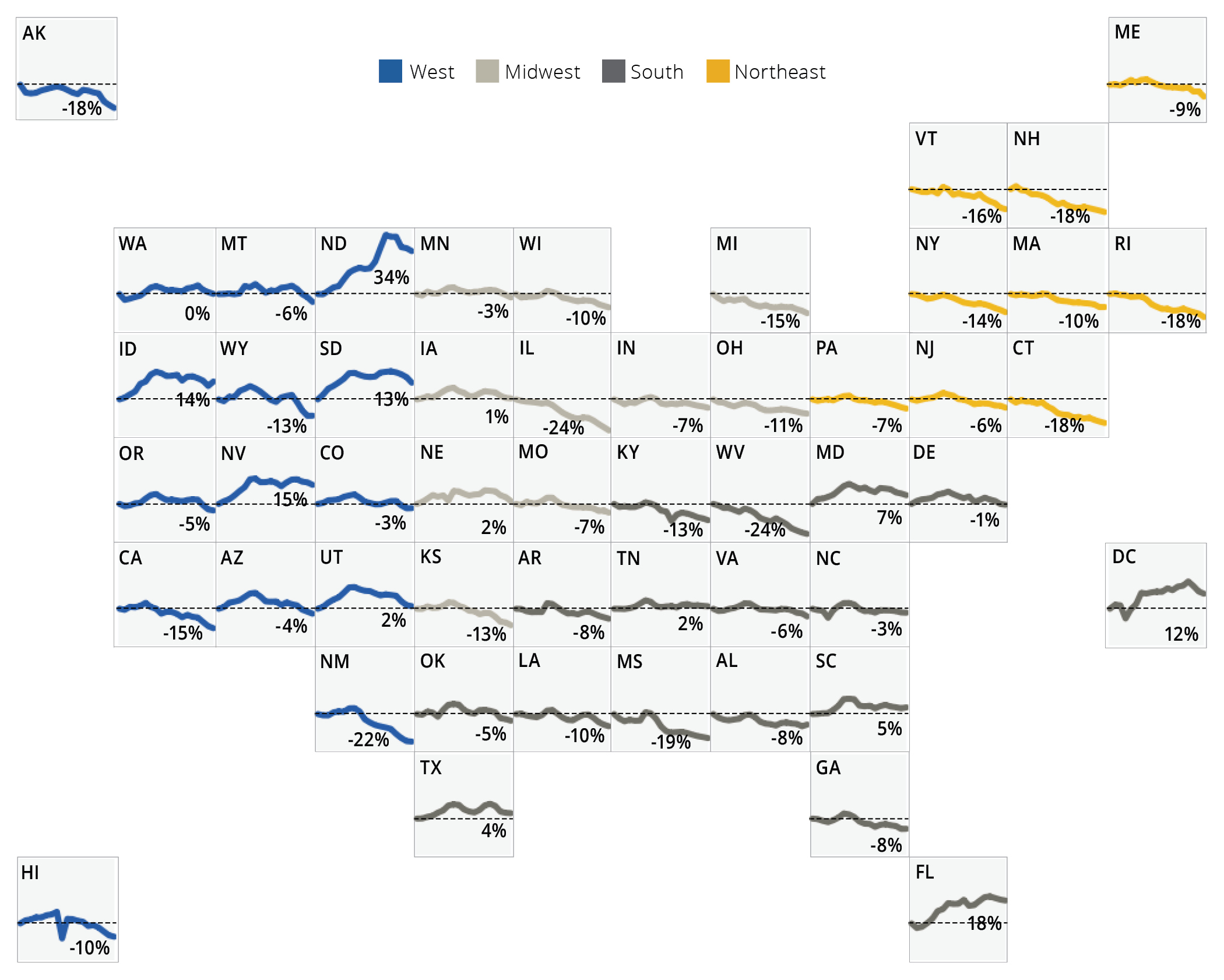

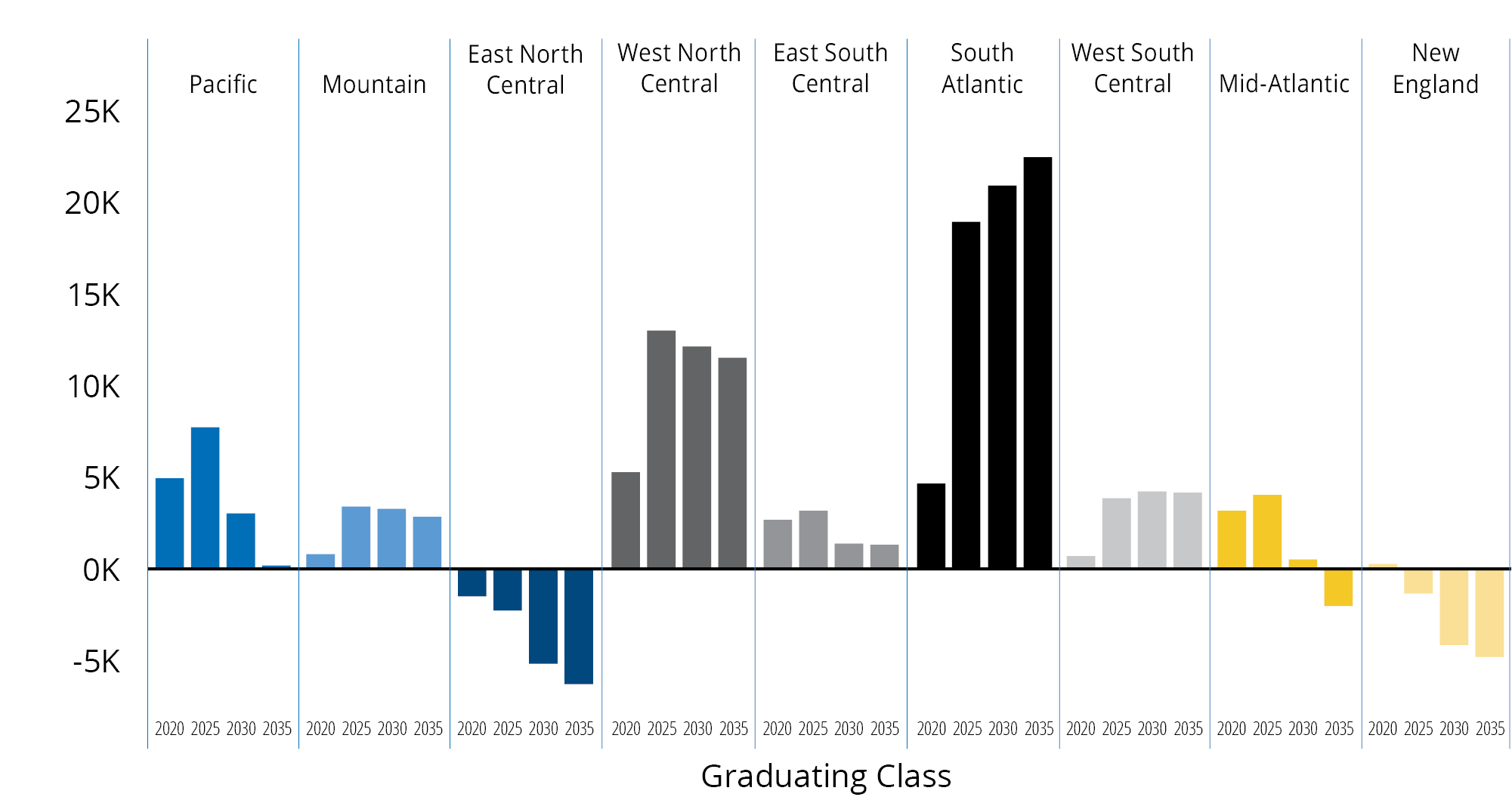

State Variation Leads to the National Net Balance; Contraction Begins Around the Country Mid-Decade

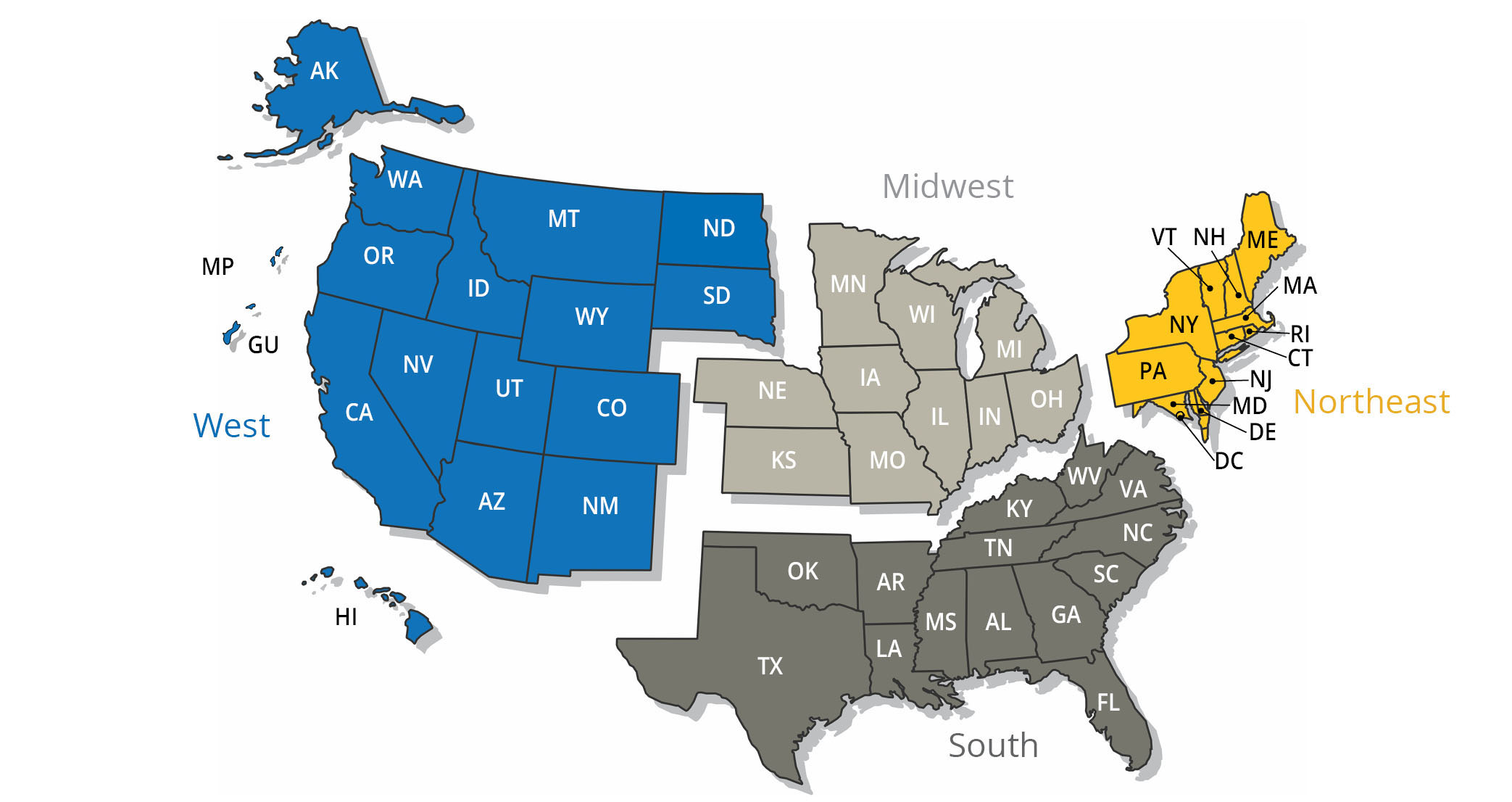

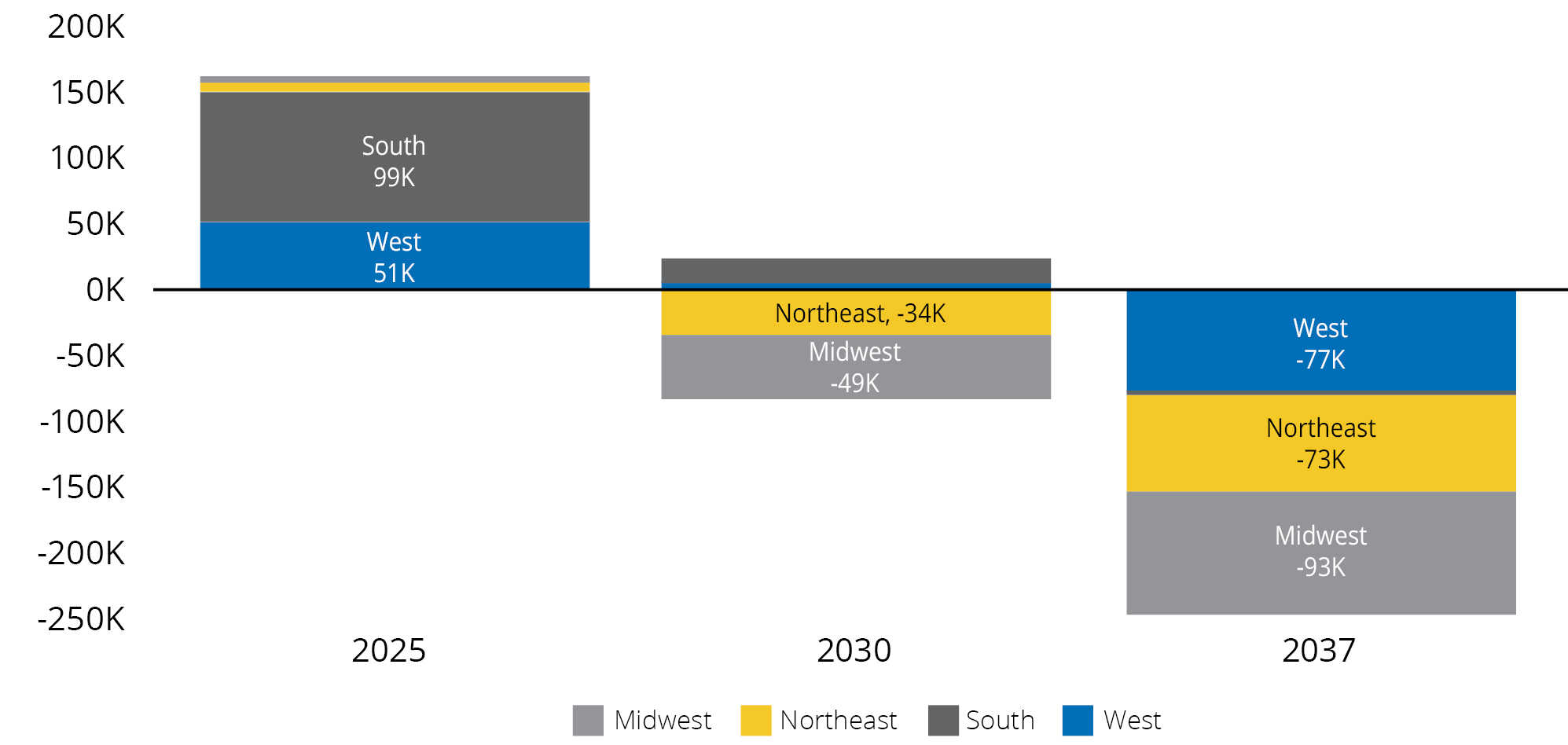

WICHE produces separate projections for four main regions as defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, and also for slightly modified Western and Midwestern regions to account for North Dakota and South Dakota being member states to both the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) and the Midwestern Higher Education Compact (MHEC). In the charts here, the regions are defined based on North Dakota and South Dakota in the Western region (see Figure 2a).[8]

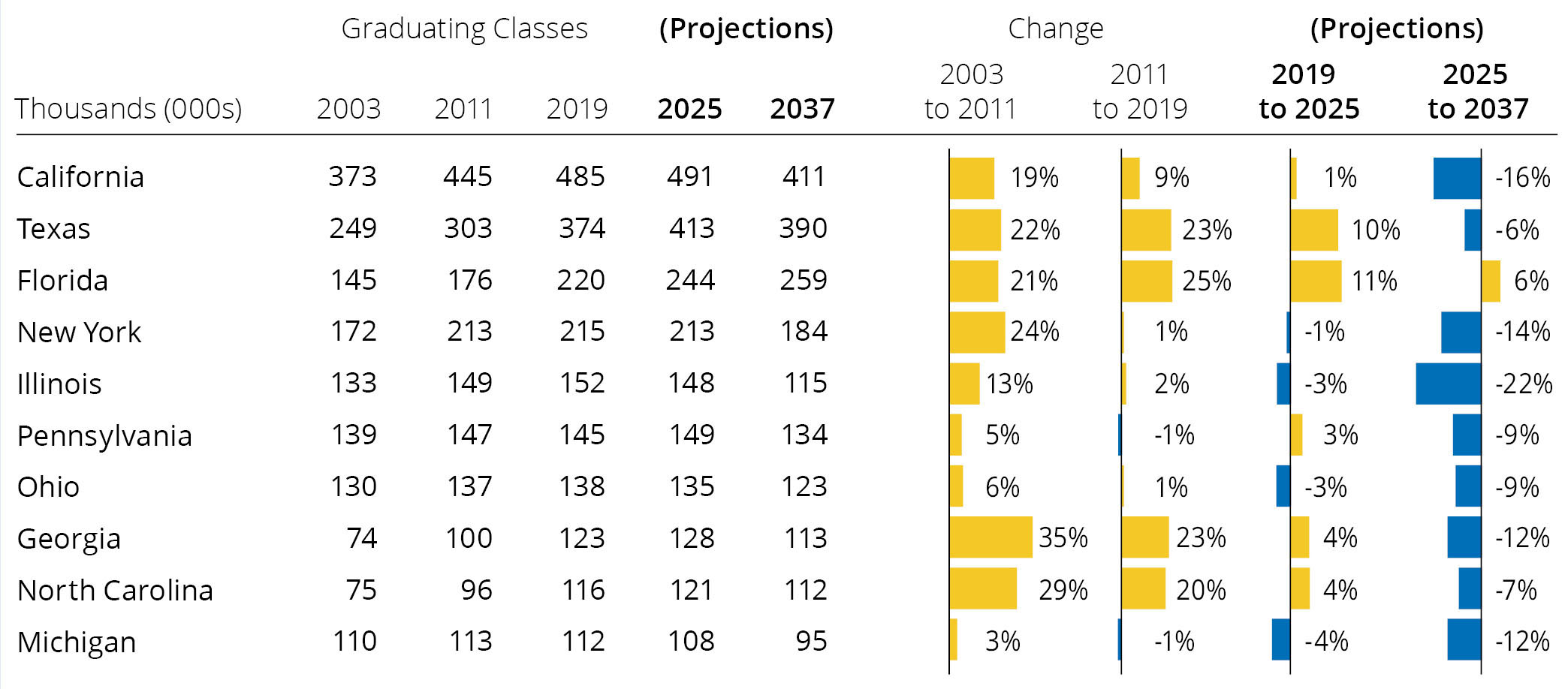

There is substantial trend variation in the state-by-state projections of high school graduates from the last reported year of total public and private high school graduates, Class of 2019, to the graduating classes projected through the mid-2030s (Figures 2b and 2c). States with increasing numbers of high school graduates balance states with projected lesser increase, or decline, in the number of high school graduates. This variation leads to the national balance of high school graduates, and factors in shifting and heightening competition for recent high school graduates across the country. Among the 10 states that produce more than half of the total U.S. high school graduates, most are projected to be generally stable with slight increases or decreases in class size, over the next five years through about 2025 (Figure 2d).[9] And then eight of these top 10 graduate producing states are projected to experience contracting or successively smaller graduating classes after 2025.

Notes: In these projections, the U.S. includes the 50 states and District of Columbia. Projections are also produced for Puerto Rico in the detailed data, but not included in U.S. figures. The Western region includes the U.S. territories and freely associated states affiliated with the WICHE region (including Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands), but data were not available at the time of publication to provide projections for them.

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis. Note: The percent change listed in each box represents the projected change in graduates from 2019 to 2037.

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis. Note: See Figure 2a for states included in each region.

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis.

The Southern region as a whole is projected to have robust graduate production throughout the projections, notwithstanding variation by state. Texas and Florida are predicted to have larger high school graduating classes (compared to the Class of 2019) in virtually every projected year, even beyond 2025. The birth declines only dampen their strong growth rates in the outer years, but do not cause actual declines compared to the number of graduates in the Class of 2019. Maryland, South Carolina, and Tennessee also contribute notably to the region’s projected strong production of graduates.

Most of the states in the Midwestern region are projected to produce fewer graduates by the mid-2030s than they currently do. Illinois and Michigan experienced declining numbers of graduates, and Ohio graduate numbers were stagnating, even before the Class of 2019 graduated. And these three Midwest states are projected to experience perpetually decreasing class sizes. Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska are projected to offset the overall decline, until they also experience contraction after peaks around 2025.

About half of the states in the Northeastern region are projected to have stagnant or declining graduate numbers in most or all years that are projected. Pennsylvania, New York, and New Jersey are projected to hold steady or have slight increases in the number of graduates, until the birth declines take effect in the mid-2020s, after which the regional downturns sharpen.

As for the Western region, California of course contributes strongly to the regional, and national, trend. The number of California graduates continued to increase heading into the projections, but at about half previous rates of increase: total California high school graduates increased 2 percent annually, on average between 2003 and 2011, and 1 percent annually, on average between 2011 and 2019. Predicted stagnation in high school graduate numbers for California, and then predicted contraction, draws down the net increase in high school graduate production that is otherwise predicted for the West region by the relatively smaller-population states of the Mountain West and WICHE member states North Dakota and South Dakota.

While the foundation for most states’ projections are overwhelmingly determined by the sheer numbers and composition of their existing youth populations, these projections may still be subject to the impacts of COVID-19. And, the educational impacts of COVID-19 are unlikely to be even or uniform across states.

The Shift to Substantially More Diverse High School Graduating Classes Will Continue

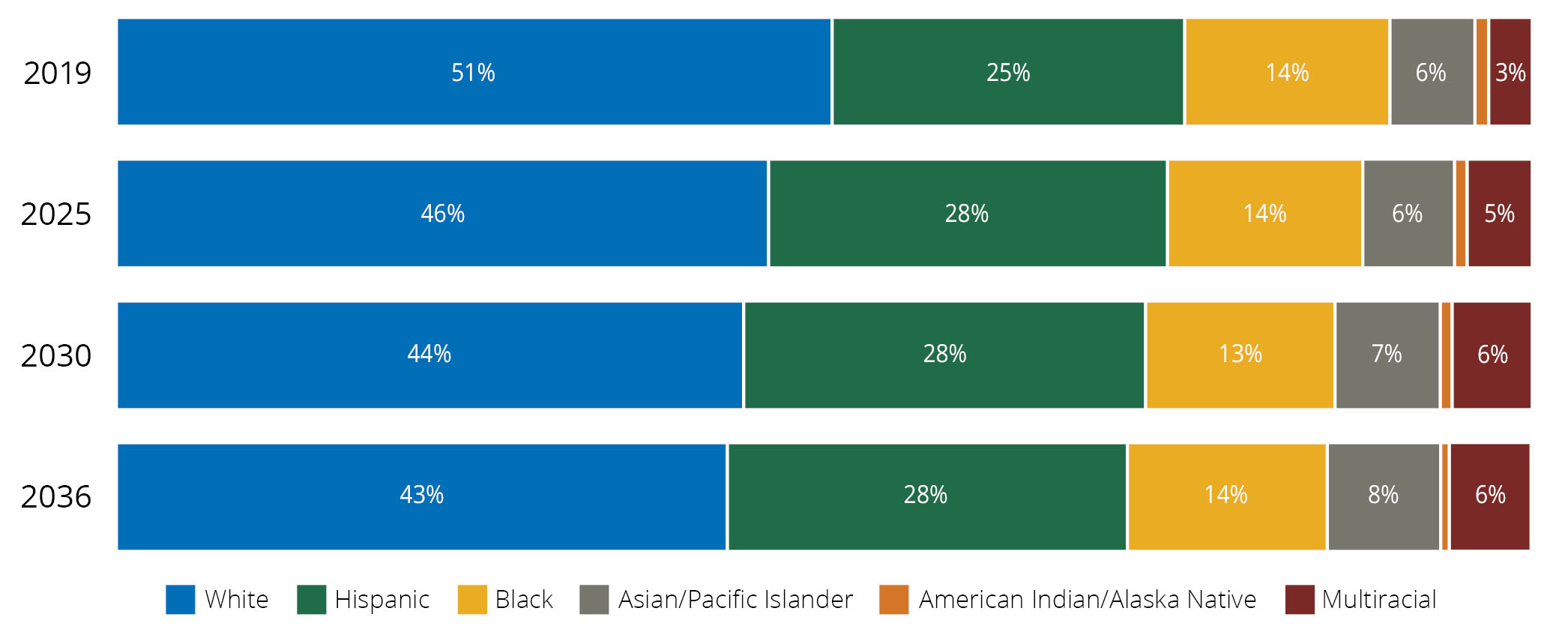

Projections for the racial/ethnic distribution of U.S. high school graduates will reflect the strong increases in high school graduation that have occurred in recent years. What used to be the coming diversity of U.S. graduates is now reality. Among the 90 percent of Class of 2019 high school graduates who were from public schools and for whom race/ethnicity data are provided: 51 percent of U.S. public high school graduates were White non-Hispanic, 25 percent were Hispanic of any race, 14 percent were single race Black non-Hispanic, 6 percent were single-race non-Hispanic Asian or Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (of these, 6 percent were Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander graduates), 3 percent were non-Hispanic multiracial, and 1 percent were single-race non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (Figure 3).

Figure 3. U.S. Public High School Graduates, by Race/Ethnicity, Class of 2019 (reported) and Classes of 2025, 2030 and 2036 (projected)

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis. Notes: American Indian/Alaska Native from U.S. Public or Bureau of Indian Education schools average 1 percent of the total. Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander graduates as a separate category average 0.35 percent of the total.

The first public high school graduating class that is no longer White non-Hispanic majority may be coming in the next year or two, with Class of 2021 or 2022, according to the projections. And, it is projected that by the Class of 2036, there will be no majority race/ethnicity among public high school graduates (this is the last year that race/ethnicity of public high school graduates can be projected using available data about U.S. births by race/ethnicity). By the Class of 2036, 57 percent of U.S. public high school graduates are projected to be of a racial/ethnic identity other than White non-Hispanic. At least eight states are predicted to pass the 50 percent non-White share mark over the course of the projections, joining the 15 states who by the Class of 2019 had graduating classes comprised of more than half non-White graduates. Consequently, how well the education system serves students of color factors heavily in overall graduate trends.

In these projections, race/ethnicity is provided for public high school graduates according to the federal reporting categories for aggregated educational data. WICHE acknowledges that these broad race/ethnicity categorizations may be lacking for describing and understanding the wide range of high school graduates. At a minimum, there may be some value from these categorizations for purposes of planning and evaluation. Furthermore, these categories provide some relevant, albeit imperfect, information for attention to racial equity.

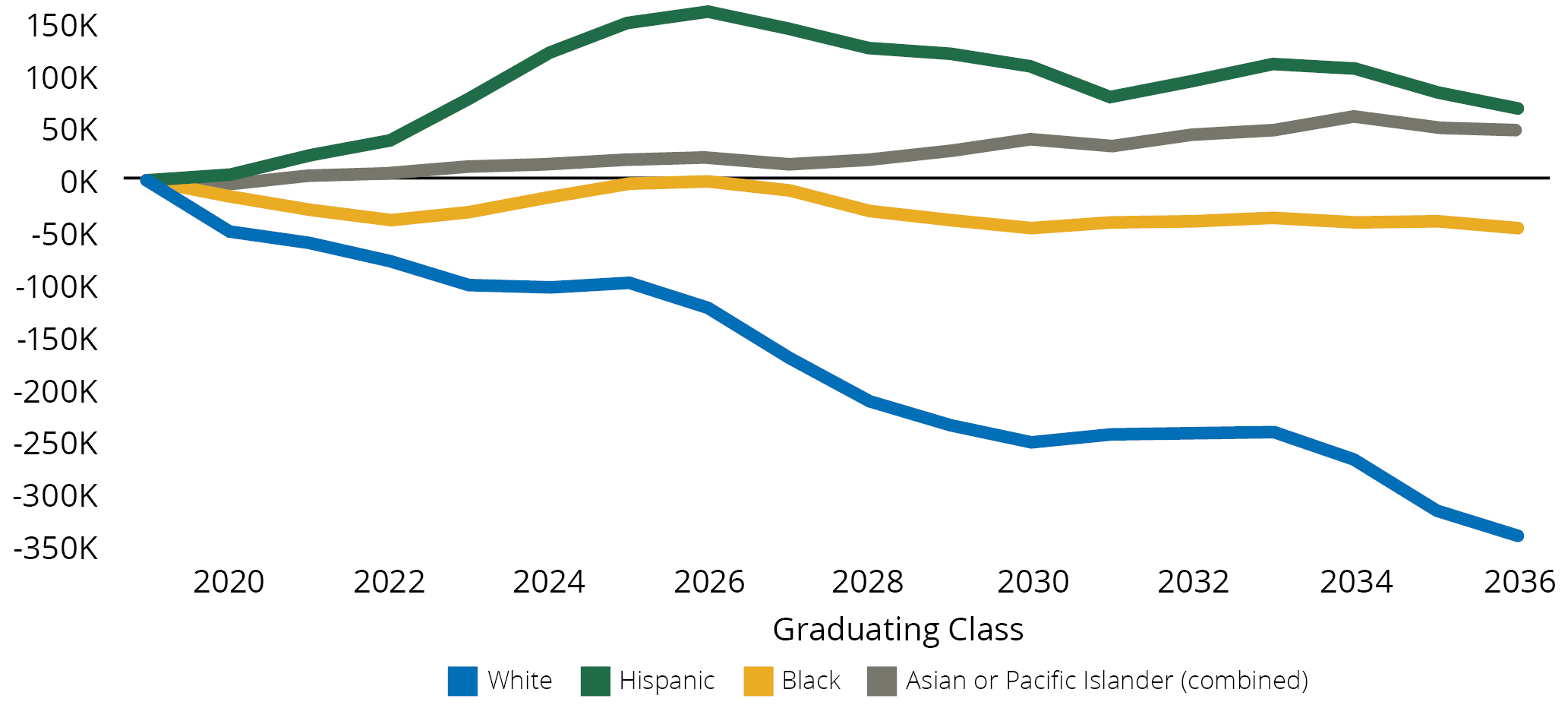

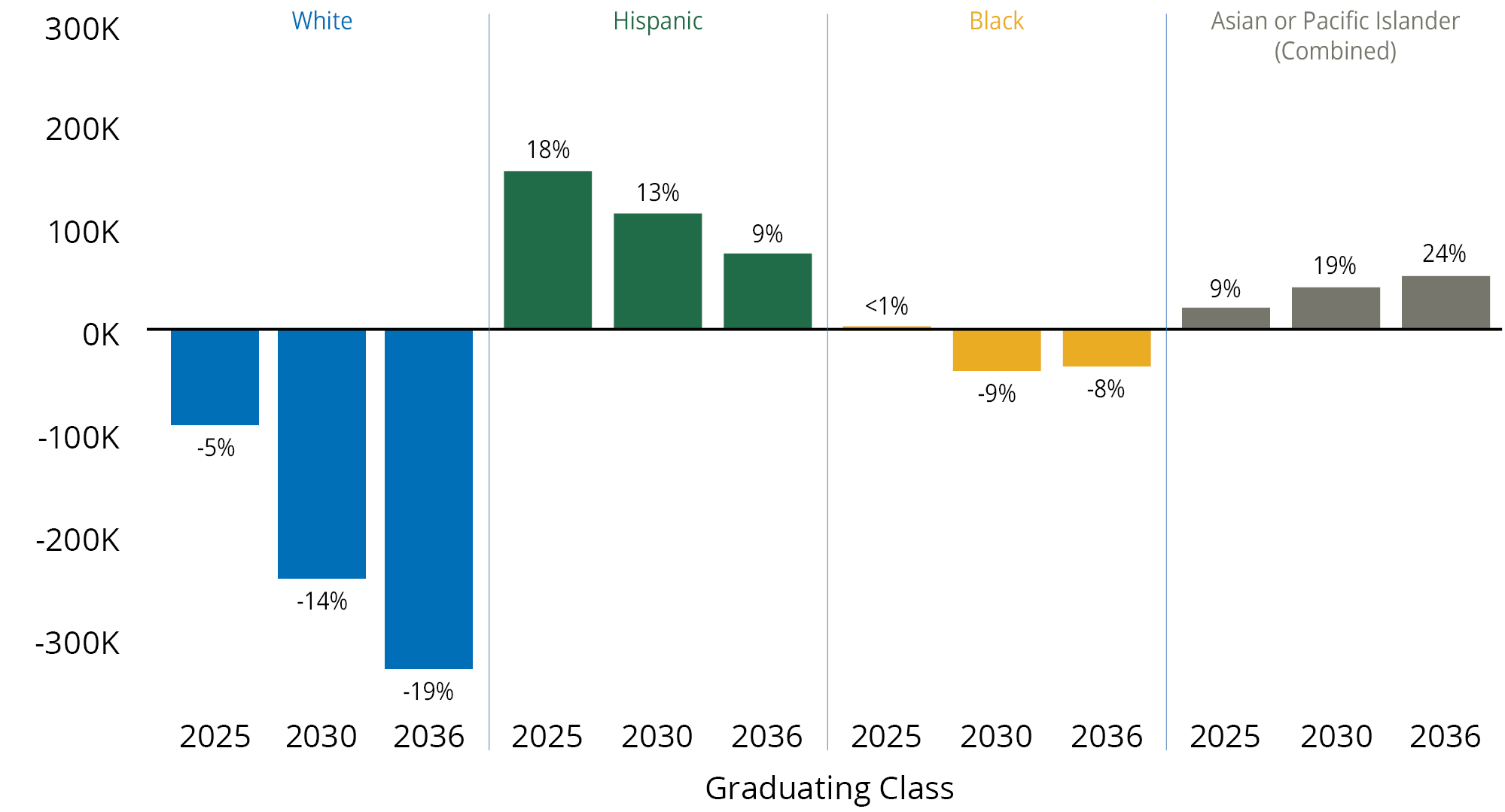

Single Race White non-Hispanic Public High School Graduates

Figure 4 shows the changes in U.S. public high school graduates predicted for future years compared to the Class of 2019, by race/ethnicity. Nationally, White non-Hispanic high school graduates were confirmed as declining in number since the Class of 2008, dropping from a high number of 1.9 million at that point to about 1.7 million by 2019, a decrease of 9 percent before heading into the projections. Roughly 300,000 fewer White non-Hispanic public graduates are projected, nationally, by the Class of 2036 (19 percent fewer). Thirty-three states are projected to have fewer White non-Hispanic public high school graduates in all future years (or only experience single year marginal increase). Correspondingly, White non-Hispanic public high school graduates are projected to be less than half of all public high school graduates in virtually half of the states (plus District of Columbia) in the early to mid-2030s.

The race/ethnicity of the approximately 10 percent of U.S. high school graduates from private high schools is not provided in the available data, and therefore their contribution to the numbers of high school graduates is not quantified in the trends described here by race/ethnicity for public high school students. However, summary data about private school student populations indicates that a majority of private high school graduates are likely to be White non-Hispanic (see Private high school graduates section below), and could therefore be expected to offset the decreasing numbers of White non-Hispanic public high school graduates. Further, a portion of the projected private high school graduates will also increase the number of projected non-White public high school graduates.

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis. Notes: Showing White non-Hispanic, Hispanic of any race, Black non-Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander (combined) non-Hispanic. Figure 5a shows additional race categories.

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis. Notes: Showing White non-Hispanic, Hispanic of any race, Black non-Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander (combined) non-Hispanic. Figure 5b shows additional race categories.

Hispanic Public High School Graduates (of Any Race)

Meanwhile, the sheer largest numeric projected increases of graduates are Hispanic public high school graduates. The number of Hispanic public high school graduates overtook the number of Black non-Hispanic public high school graduates, nationally, in the Class of 2008. And, by the Class of 2019 there were almost two Hispanic public high school graduates, nationally, for every Black public high school graduate. The number of U.S. Hispanic public high school graduates is predicted to increase 19 percent more by the Class of 2026 (just after the overall peak in the Class of 2025), to just over 1 million. In at least 35 states, the number of Hispanic public high school graduates is projected to increase 25 percent or more by the Class of 2025, compared to the Class of 2019. And while the birth declines will dampen this impressive growth trend and lead to some downturn after 2025, nationally, at least 9 percent more Hispanic public high school graduates are projected for the Class of 2036 than were counted in the Class of 2019. Correspondingly, in 39 states the number of Hispanic public high school graduates will still be at least 10 percent higher in the Class of 2036 than were reported in the Class of 2019. And, the Class of 2036 is projected to have at least 50 percent more Hispanic public high school graduates than the Class of 2019, in 23 states.[10]

Single Race Black non-Hispanic Public High School Graduates

The third largest racial/ethnic category of public high school graduates is Black non-Hispanic graduates. In fact, Black public high school graduates are greater in number than private high school graduates (for whom race/ethnicity is not known). The number of Black U.S. public high school graduates is projected to remain relatively stable in number from the Class of 2019 to the Class of 2025 (0.4 percent increase). And then the number of Black U.S. high school graduates is projected to decline in similar magnitude as the overall trend, with about 8 percent fewer Black public high school graduates projected for the Class of 2036 than were reported in the Class of 2019, nationally. This national balance results from variation across states, such as shown in Table 2 among key states for Black public high school graduates.

Table 2. Black Public High School Graduates, Reported Number and Percent of Each States’ Class of 2019 Public High School Graduates, and Projections through Class of 2036

| Location | 2019 | 2025 | 2030 | 2036 | Percent of Public School Graduates, Class of 2019 |

| Texas | 43,950 | 48,690 | 45,860 | 52,020 | 12% |

| Georgia | 41,120 | 43,630 | 39,470 | 39,850 | 36% |

| Florida | 40,050 | 38,210 | 36,680 | 37,180 | 21% |

| New York | 30,580 | 27,840 | 23,840 | 21,550 | 17% |

| North Carolina | 27,410 | 27,140 | 24,720 | 25,390 | 25% |

| California | 24,190 | 20,690 | 18,540 | 16,300 | 6% |

| Illinois | 20,700 | 19,540 | 16,350 | 15,490 | 15% |

| Maryland | 19,650 | 21,100 | 19,600 | 18,980 | 34% |

| Virginia | 19,050 | 18,870 | 16,860 | 16,760 | 22% |

| Louisiana | 18,250 | 17,670 | 15,400 | 14,810 | 43% |

| South Carolina | 16,030 | 17,270 | 15,210 | 14,440 | 33% |

| Alabama | 16,360 | 15,520 | 14,250 | 14,310 | 33% |

| Tennessee | 13,740 | 13,710 | 12,550 | 12,580 | 21% |

| Mississippi | 13,830 | 13,920 | 10,860 | 10,520 | 47% |

| Delaware | 2,890 | 3,030 | 2,790 | 2,810 | 31% |

| District of Columbia | 2,310 | 2,740 | 2,640 | 2,420 | 71% |

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis.

Whereas many states are projected to see decreased numbers of Black public high school graduates over the course of the projections, at least 20 states are projected to have greater numbers of Black public high school graduates by the Class of 2036 than were counted in the Class of 2019.

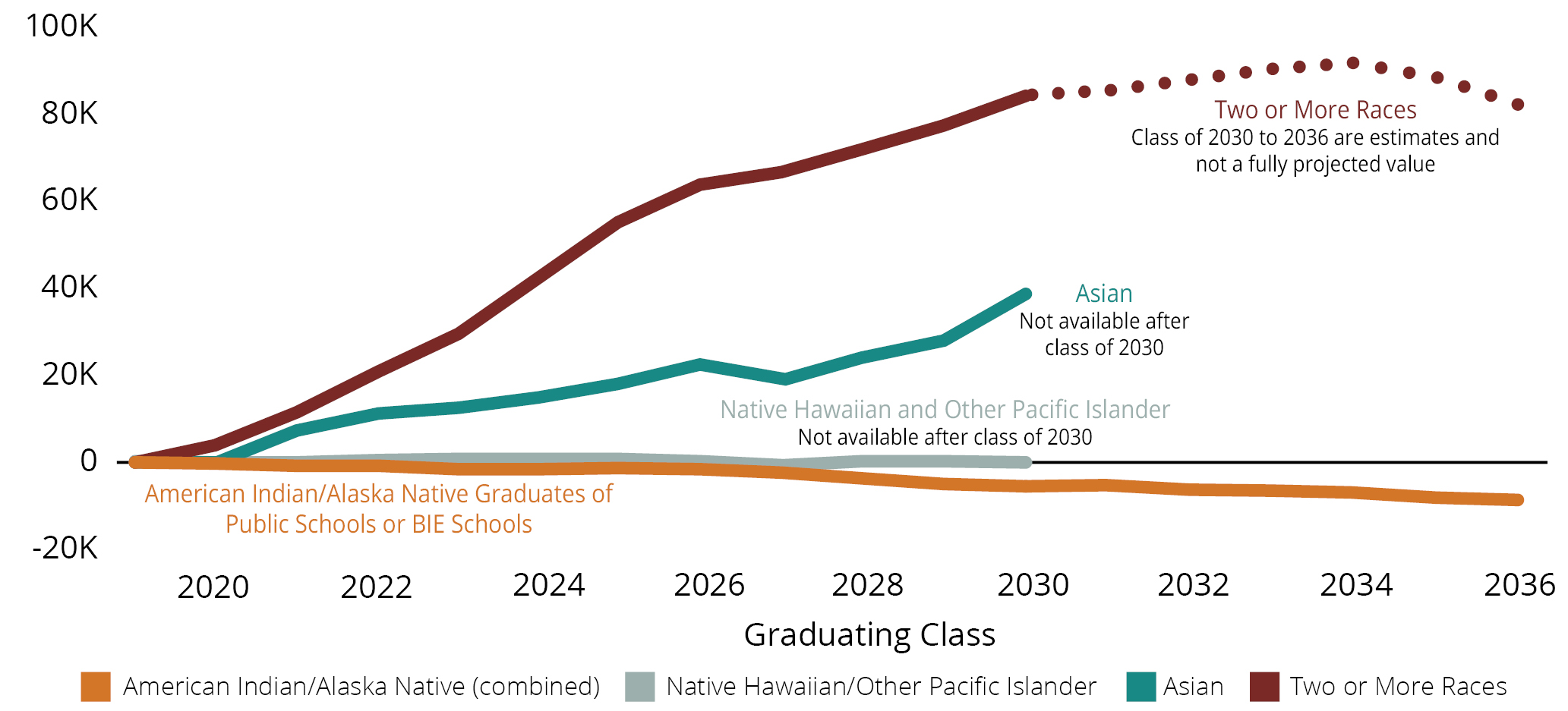

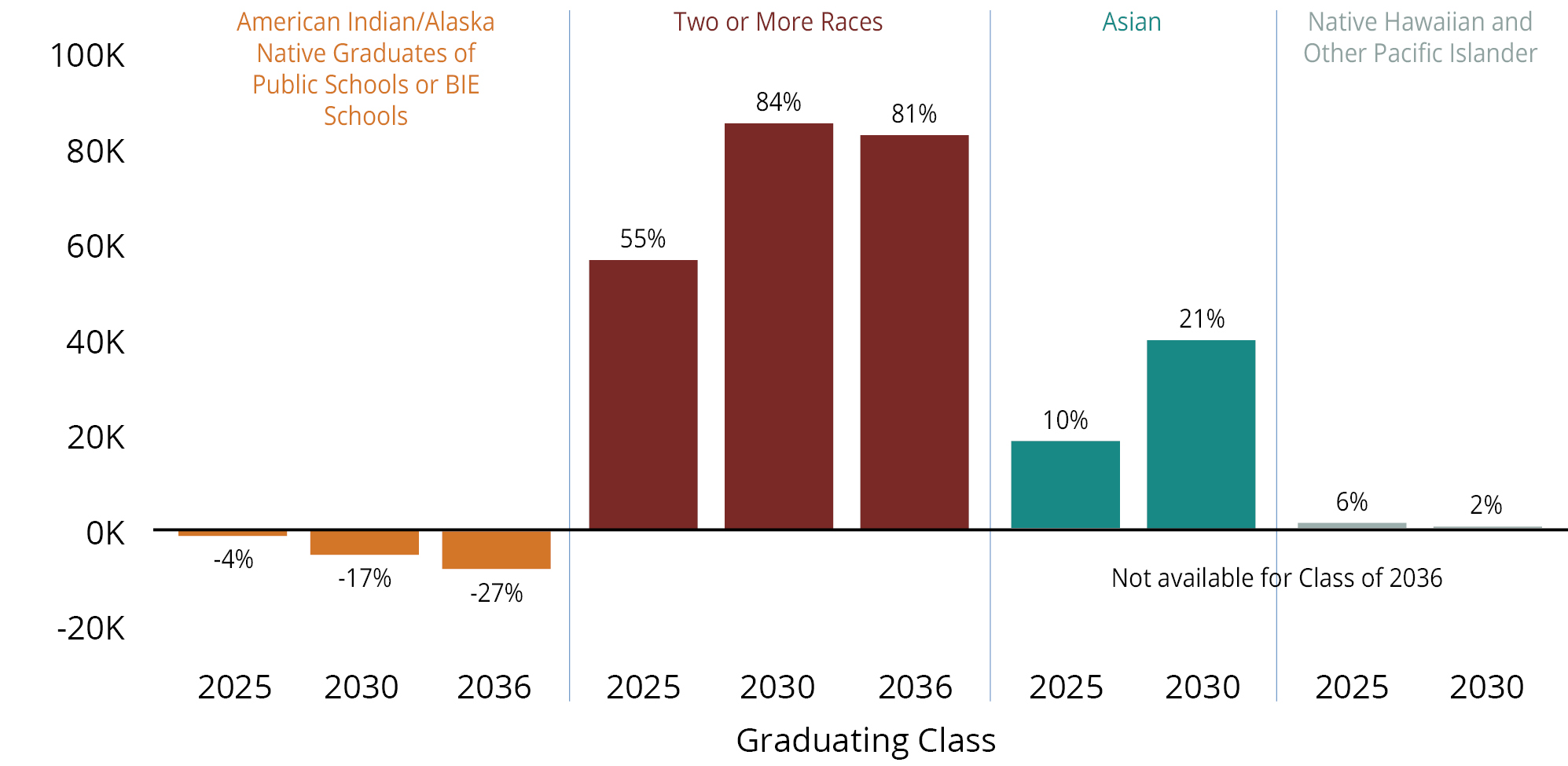

Single Race Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander Public High School Graduates

In this 10th edition, WICHE provides projections for public high school graduates categorized as Asian separate from those categorized as Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, through the Class of 2030, as well as a combined total of Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander public high school graduates for all years through the Class of 2036.[11] Nationally, the combined number of Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander graduates is projected to increase throughout the course of the projections. Thirty percent more Asian/Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander public high school graduates are projected by the Class of 2034 compared to 2019; a small drawback of 4 percent is then projected for the last two graduating classes (2035 and 2036). The number of Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander public high school graduates is projected to increase about 4 percent through the Class of 2025, at least (Figure 5). However, public high school graduates categorized as Asian dominate and are projected to average about 93 percent of the combined total Asian or Pacific Islander graduates throughout the years projected (through Class of 2030).

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis. Notes: Showing American Indian/Alaska Native non-Hispanic from Public Schools and Bureau of Indian Education Schools (combined), Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander non-Hispanic separately (through Class of 2030), and Two or More Races non-Hispanic (projected through Class of 2030, then estimated through Class of 2036).

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis. Notes: Showing American Indian/Alaska Native non-Hispanic from Public Schools and Bureau of Indian Education Schools (combined), Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander non-Hispanic separately (through Class of 2030), and Two or More Races non-Hispanic (projected through Class of 2030, then estimated through Class of 2036).

Non-Hispanic Public High School Graduates of More Than One Race

In this 10th edition, WICHE provides projections for public high school graduates categorized as non-Hispanic and more than one race (multiracial).[12] Non-Hispanic multiracial graduates were 3 percent of U.S. public high school graduates in Class of 2019 (103,200 graduates). Non-Hispanic multiracial graduates are projected to increase in number by 84 percent by Class of 2030, at which point multiracial graduates are projected to be almost 6 percent of public high school graduates (190,000 graduates).

State-level projections for this category of graduates can be somewhat more speculative, as the projection methodology identifies apparently large changes in what are often relatively small numbers of students and can carry forward possibly implausible rates of increase. The data indicate that more than half the states may experience a doubling, or greater percent increase, in public high school graduates categorized as non-Hispanic multiracial, between Class of 2019 and 2030. WICHE observes from the data that it may take more time for this category of students to settle into a pattern that better reflects multiracial student identifications and less so the evolution of a data category.

Single Race Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native Public High School Graduates

The projections for American Indian/Alaska Native graduates from U.S. public high schools show a consistent reduction in numbers. The number of reported American Indian/Alaska Native graduates from public schools decreased 9 percent between 2010-11 and 2018-19 (from 33,000 to 30,000). Whereas other public high school graduate populations are peaking around 2025, 6 percent fewer American Indian/Alaska Native graduates are projected as high school graduates from U.S. public schools by this point. And, 28 percent fewer are projected by 2036, compared to 2019.

The projected severity of declines for graduates with American Indian or Alaska Native identity likely mischaracterize what would appear to be population growth, from other data. What is able to be projected from public school data might be better described as: there is a predicted decline in the number of high school graduates categorized as single-race non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native. A strong portion of students with an American Indian/Alaska Native identity may be included among the increasing numbers of multiracial public school graduates.

For example, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, the overall U.S. population of individuals classified as American Indian and Alaska Native (not limited to children) increased at a faster rate than the total population between 2010 and 2019, when one incudes those who were single race American Indian/Alaska Native or in combination with another race.[13] However, only individuals classified as single-race American Indian/Alaska Native will be captured in the federal racial/ethnic definitions for aggregate student data. Since, according to U.S. Census Bureau data, nearly half of the American Indian and Alaska Native population reported multiple races, a strong portion of students with an American Indian or Alaska Native identity are therefore likely to be included among the increasing numbers of multiracial students.[14] Furthermore, a disproportionally higher rate of the American Indian/Alaska Native youth population would be classified as Hispanic (30 percent compared to 25 percent of youth overall) if classified by the education reporting categories. Thus, an additional portion of students who could be identified as American Indian/Alaska Native may instead by represented in the Hispanic category in these projection data.[15]

Estimated Additional American Indian High School Graduates from Bureau of Indian Education Schools

Students who attend Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) bureau-run and tribally-controlled schools are not covered by the primary public school data used for these projections, so WICHE estimated their numbers for these national projections.[16] Students at BIE schools may be graduating at different rates than American Indian/Alaska Native students in public schools, but those precise graduation rate data are not available.[17] So, WICHE used the available three most recent years of student enrollment data for BIE schools to estimate what additional number of American Indian graduates there might be, nationally, if an approximate number from BIE schools were added to the number from public schools (WICHE estimated the additional number from BIE schools based on the ratio of 12th graders to graduates for American Indian/Alaska Native students at public schools; see Technical Appendix for more information).[18] While the estimated higher number of American Indian/Alaska Native graduates from either public schools or BIE schools does not specifically address the race categorization issue, these estimates indicate that may be an average of 7.7 percent more American Indian/Alaska Native graduates, annually, over the course of the projections than would be projected from public schools alone. (Because BIE schools data are not available for all years, this combined estimate is only provided as a supplemental series in the U.S. projections and not added to the U.S. grand totals or any state projections.)

Private High School Graduates: Projected to Trend Upward and Prop Up the U.S. Total High School Graduates—but Future Hard to Predict

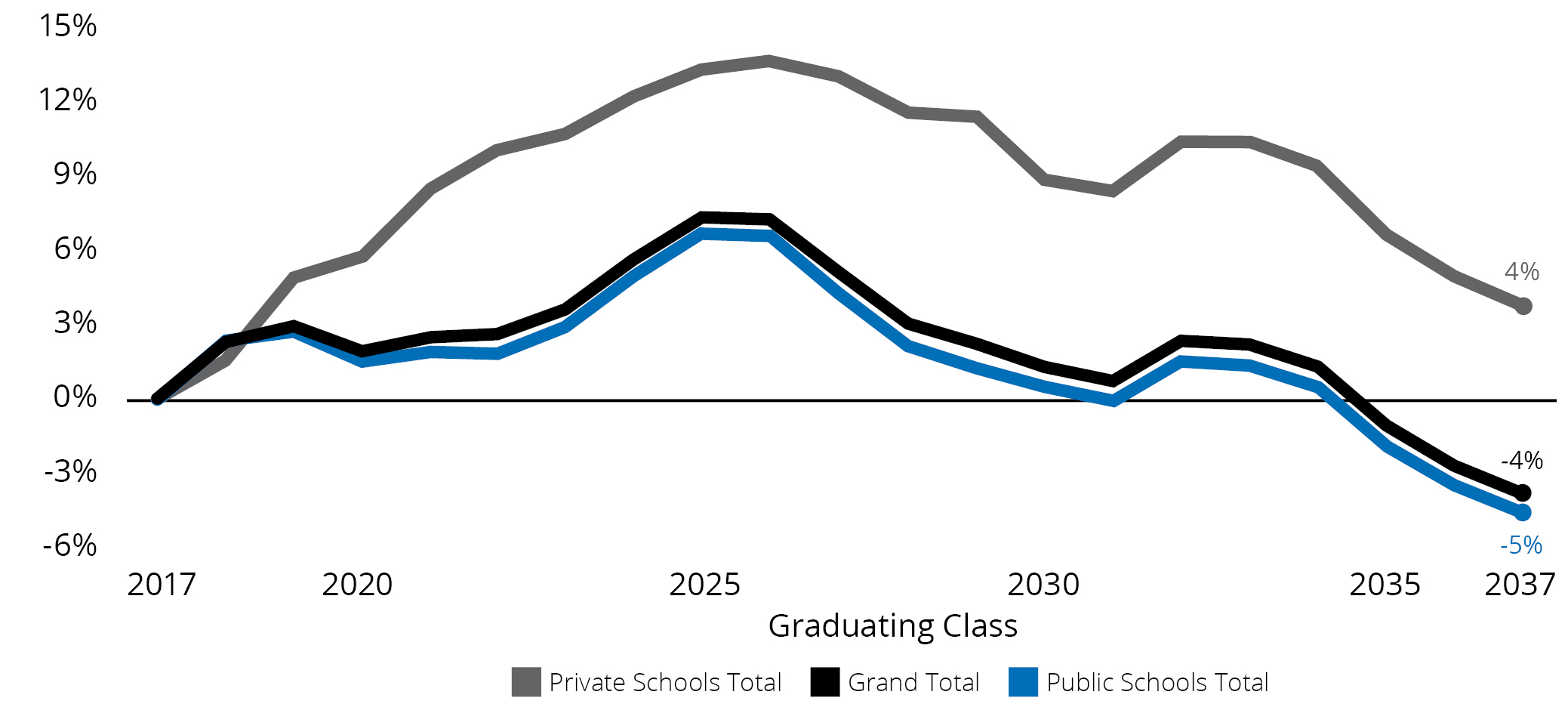

The most recent data for K-12 private schools predict a very different future than would have been anticipated from patterns of enrollment contraction that had been emerging in the data for years prior.[19] The overwhelming pattern for years had been driven by decreasing Catholic school enrollments, and then there were several years of even sharper private school enrollment declines coincident to the Great Recession.[20] However, data for school years 2013-14 to 2017-18 (the most recent reported data available for private schools) indicate robust returns to the private school sector since school year 2010-11, which change the projected direction for private high school graduates.

Nationally, private high school graduates are now projected to increase in number by as much as 13 percent from Class of 2017 to 2025 (Figure 6). Then, even as the number of U.S. public school graduates is projected to begin contracting after 2025, 9 percent more private high school graduates are projected by Class of 2030 compared to Class of 2017. Private high school graduates are projected as 10-11 percent of U.S. total high school graduates over the course of the projections. So, while public school populations still drive the overall number and patterns for total U.S. high school graduates, these positive private school trends contribute some “cushion” to the overall downward trend that is predicted by annual decreases in the number of young children beginning with 2007.

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis; see Technical Appendix for details about the private school data source.

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis; see Technical Appendix for details about the private school data source.

Source: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, Knocking at the College Door, 10th edition, 2020. WICHE projections and analysis; see Technical Appendix for details about the private school data source. See endnote 8 for information about U.S. Census regions and divisions.

(View private high school graduates by state)

The enrollment increases driving these projected trends occurred rapidly. Whereas, nationally, private elementary and middle school enrollments declined by more than 20 percent and high school enrollments by 2 percent from school year 2001-02 to 2011-12, from school year 2011-12 to 2017-18 they increased by 7 percent and 15 percent, respectively. Some issues with the survey data used for the state-level private school projections are discussed in the Technical Appendix. But these issues do not appear to affect the national and regional estimated numbers of private school students.

Ultimately, even if the recent resurgence for U.S. private schools indicated from the available data is reliably correct, these rapid and strong trend changes are not ideal for making projections. The progression methodology will mathematically carry forward recent past trends, even if the magnitude of change would not necessarily be sustained in actuality over the coming 15-17 years. The release of school year 2019-20 data for private schools is not expected until 2021; WICHE will monitor those data to assess whether the increases between school year 2011-12 and 2017-18 were sustained as projected for the Class of 2018 to 2020 and beyond. But it will be several years before data indicate how private schools fared in relation to COVID-19 and ongoing economic instability.[21]

Differing Private School Graduate Trends by Region

Figure 6c (above) shows which regions are driving the national trend of increasing private school graduates (presented by the nine U.S. Census geographic divisions). Fewer private high school graduates are projected from the East North Central (Great Lakes) and New England regions, although not in the sheer large numbers that were previously projected. Private high school graduates are projected to increase for virtually all other parts of the country through the Class of 2030. A downturn in private high school graduates from the Mid-Atlantic is projected by the early 2030s (from New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania). Even though the South is now the dominant region for overall growth of high school graduates, the substantial increases from the South appear to be driven not only by the increasing number of children but also private school expansion.

Changing Mix of Private School Students by School Type

It is not possible to specifically produce projections of high school graduates by type of private school from the available data, but WICHE can estimate enrollment trends by type of private school at the national level. Table 3 shows quite different enrollment patterns that occurred between school year 2001-02 and 2011-12, compared to those between 2011-12 to 2017-18 (the most recent available year of private school data), for private schools categorized as Catholic, other religious or nonsectarian (many nonsectarian private schools are also considered ‘independent schools’, but they are not synonymous). Whereas previous trends were dominated by the decreasing Catholic school portion, the projections for private school graduates from 2020 to 2037 are strongly influenced by recent rapid enrollment increases for non-Catholic religious private schools and nonsectarian schools.

Table 3. Private School Student Enrollments SY 2001-02 to 2017-18, by Type of Private School

| School Year 2001-02 to 2011-12 | School Year 2011-12 to 2017-18 | |||||||

| Grades 1 to 8 | Grades 9 to 12 | Grades 1 to 8 | Grades 9 to 12 | |||||

| Percent Change | Share, 2011-12 | Percent Change | Share, 2011-12 | Percent Change | Share, 2017-18 | Percent Change | Share, 2017-18 | |

| Catholic | -29% | 43% | -5% | 48% | -1% | 40% | 9% | 45% |

| Other Religious | -17% | 40% | 2% | 32% | 11% | 41% | 13% | 31% |

| Nonsectarian | -6% | 17% | 8% | 22% | 22% | 19% | 26% | 24% |

Source: WICHE estimates and analysis from Private School Universe Survey data (https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/pss/). See Technical Appendix for details about the private school data source.

Race/Ethnicity of Private School Students

Finally, the underlying data source for the private school series only provides the total number of K-12 students by race/ethnicity, and not detail by grade-level or for graduates. So, WICHE is not able to include private school students in the race/ethnicity series of these projections. But, NCES estimates that 67 percent of private elementary and secondary school students in fall 2017 were White, 11 percent were Hispanic, 9 percent were Black, 6 percent were Asian, and 5 percent were students of two or more races.[22] Therefore, just as these projected numbers of private school graduates add to and help buoy up the total number of high school graduates, so might they supplement to an extent the trends indicated by race/ethnicity. By extension, the largest portion of these private high school graduates might offset some of the declines of White public high school graduates – and increase the numbers of graduates already projected from public schools for the other public school race/ethnicity categories.

Improvements in High School Graduation Rates Fueled the Robust Numbers of Graduates

From the early 1990s to 2010, the number of U.S. total high school graduates increased 2 percent per year, on average. An imminent decrease of these strong annual increases in high school graduates has been the subject of previous editions of these projections and predicted by others.[23] The updated data indicate that, in fact, between the Class of 2010 and 2019, the average annual rate of increase in U.S. total high school graduates declined to 1.1 percent. However, according to the data WICHE analyzed, it appears that graduation rate improvements that occurred over the past decade yielded more high school graduates even while the overall rate of increase in youth is tightening.[24] Some shifting of students to the private school sector also appears to contribute to some of the observed increases.

WICHE analyzed the reported numbers of high school graduates between the Class of 2013 and Class of 2019 to better understand the sources of unpredicted change since the 9th edition of these projections and to identify the factors that are driving these newly issued projections. The 9th edition projections predicted 2 percent fewer U.S. total high school graduates for the Class of 2013 than were ultimately reported, increasing to a difference of 8 percent by the Class of 2017 (these are the four years of data which provided a comparison point of reported, confirmed graduates; by the Class of 2018 and 2019, private school values are projected).

Private School Portion of the Recent Increases

Private school graduates accounted for 30 percent to 58 percent of the unpredicted increase in the four years examined, amounting to between 35,000 and 81,000 more private high school graduates than were previously predicted. As discussed above, projecting high school graduates for the private school sector has become increasingly difficult.

Public School Portion of the Recent Increase, by Race/Ethnicity

Public high school graduate numbers have subsequently been reported as 1 to 6 percent more than predicted for the graduating classes of 2013 to 2019. Hispanic public high school graduates accounted for the greatest increases from what was predicted; 75,000 more Hispanic graduates (10 percent) were reported for the Class of 2019 than were predicted in the 9th edition.

The 9th edition provided public high school graduate projections by four major race categories, whereas six race categories are available in this 10th edition, so it is not possible to fully compare. Notably, about 1 percent fewer White non-Hispanic graduates were reported between classes of 2013 and 2019 than were projected in the 9th edition; 10,000 to 30,000 per year. The 9th edition did not provide separate projections for multiracial public high school graduates, rather their numbers were counted in the four main race categories. In this edition, the newly projected multiracial category accounts for the greatest quantity of graduates by race that were not previously projected, starting at 63,000 with the Class of 2013 and growing to 150,000 by the Class of 2019. By the Class of 2019, a greater number of Black, Asian/Pacific Islander and American Indian/Alaska Native public high school graduates were also reported compared to what was predicted (30,600 or 6.6 percent; 14,000 or 7.2 percent; and 2,400 or 8.4 percent, respectively).

Recent Increases in Number of Graduates Follow Increases in Graduation Rates

WICHE’s projections for the total number of high school graduates are not derived from the federally defined high school graduation rates, which states have been reporting since 2012. But, WICHE’s analysis indicates that the two graduation trends (graduation rates and the total annual number of graduates) track closely in relative magnitude.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, the U.S. average on-time graduation rate for public high school students increased from 79 percent in school year 2010–11 to 85 percent in 2017–18 (the latest information available).[25] Of course, graduation rates differ by state and subpopulations of students, but by school year 2017-18, 30 states reported an overall public school adjusted cohort graduation rate at or above this national average.[26] Comparatively, the data WICHE collected from states shows that the number of total annual U.S. public high school graduates increased 8 percent over the same period. In at least half the states, the increase in the number of total annual public high school graduates tracked within 1.5 percent of the increase in the estimated number of on-time graduates that can be derived from the adjusted cohort graduation rate data (WICHE analysis and estimates from publicly available data).[27]

The U.S. on-time graduation rates for Hispanic public high school students increased from 76.3 to 81.0 percent by 2017-18 (the latest year available). The on-time graduation rates for Black public high school students increased from 72.5 to 79.0 percent; for American Indian/Alaska Native public school students (not including students of Bureau of Indian Education schools), rates increased from 69.6 to 73.5 percent; and for Asian/Pacific Islander students, rates increased from 89.4 to 92.2 percent (rates for multiracial students not available). Over the same period, on-time graduation rates for White non-Hispanic public school students increased from 87.2 to 89.1. This improvement in rates did appear to yield positively in the number of U.S. White non-Hispanic public high school graduates by potentially reducing the predicted rates of decline predicted in their student numbers.

The COVID-19 Impact

WICHE’s high school graduate projections have always been based on retrospective data. Most years, this leads to relatively accurate projections, especially in the first few years after publication. But – in what might be the understatement of all understatements – 2020 is not “most years.” Typically, as can be seen in this edition, the biggest source of deviation from the projections are changes in how well K-12 education systems across the country serve students. As retention and graduation rates improve, WICHE’s projected numbers can fall behind the actual numbers. In the 40-year history of this work, however, our society has not experienced this type of global event with the potential to dramatically impact our nation’s K-12 educational pipeline, and in ways that are so dramatically inequitable across racial/ethnic, economic, and geographic lines.

By reflecting the recent past, these projections perpetuate the latest school attendance patterns and graduation rates. For the U.S. overall, that means a roughly 85 percent on-time graduation rate is presumed (the precise rate will vary by state and student race/ethnicity).[28] Were nothing to have intervened, the projections indicate that relatively high graduation rates would buoy up the number of high school graduates and somewhat offset the impacts of developing contraction and eventual decline in the young adult population.

However, it is not yet clear what the impact of COVID-19 and the resulting economic disruption will be. Certainly, students of all grades, ages and school type were impacted as schools rapidly transitioned to remote instruction in March 2020, including learning loss or reduction, disruption or canceling of milestone academic and extracurricular events, socioemotional or family socioeconomic changes that might have immediate or long-term achievement impacts, or even complete disengagement from school.

Some initial research has found increased graduation rates in 2020, possibly due to the economic downturn leading some students who would have stopped out to seek employment to stay and earn a diploma.[29] The authors also speculate that the loss of extracurricular activities and distractions could lead to improved completion. Yet, even with these somewhat counterintuitive findings, they are very clear that there are definitely negative impacts on some students, including a possible decline in educational quality. These short-term impacts bear watching, but it is also clear that COVID-19 is likely to have long-term and negative effects on the education system.

The trends projected using WICHE’s methodology mathematically “assume” that school attendance and graduation through school year 2021-22 (and further into the future as the nation recovers from the pandemic and economic impacts) will be roughly similar to recent years. This is looking less and less plausible, but exact impacts are not yet known. One thing is clear, however: how well the education system serves diverse student populations and low-income students has a large bearing on whether the overall number of high school graduates will vary from what is projected and by how much. This is particularly concerning given the documented impacts of COVID-19 on these communities.

Moreover, the overall graduation pattern is influenced by “the parts of the whole,” which from the available data refer largely to race/ethnicity. White non-Hispanic high school graduates are still the majority by number and have among the highest graduation rates—increasing rates of public high school graduation can only mitigate or dampen the accumulating effect of White youth population declines in the high school graduate numbers. On the other hand, almost half of U.S. school-age youth are children of color and as they age from elementary to high-school age, the number of high school students of color will increase. So, whether educational outcomes for children of color or otherwise underserved students are more negatively impacted during this time has a large bearing on whether the overall number of high school graduates will change from what is projected.

There also may be volatility in the proportion of students at public or private schools as families face economic pressure, but also concerns about in-person versus remote learning or childcare needs.[30]

Sudden, widespread shifts in education are uncommon, so it has typically been unnecessary (and beyond WICHE’s resources) to update the projections more than every 4 to 5 years, let alone annually. But increased responsiveness and frequency of information is justified and needed in this unprecedented period. WICHE is preparing and intends to issue new information about the state-level trends, and possibly adjusted projections, as newer actual data about enrollments and graduates from school year 2019-20 to 2021-22 become available. WICHE relies on a relatively straightforward projection methodology and can capitalize on this to respond as newer data become available. At the same time, some of the expected impacts from COVID-19 and the ensuing economic downturn may be much more nuanced or unclear than can be identified with the existing projection methodology or enrollment and graduate count changes, requiring a new modeling approach. And, these impacts will be intersecting with and overlapping across multiple sectors, perhaps requiring new approaches.

The First Projected Year, Class of 2020, is Less Likely to Show Impacts from COVID-19

The number of high school graduates projected for Class of 2020 would probably only be substantially different from the number ultimately reported, if high school seniors who were on-track to graduate by March 2020 were so impacted by the disruptions in the last several months of the spring semester that it impeded their ability to complete requirements for receiving their diploma. And this scenario would suggest fewer than projected graduates. Given that many school districts provided substantial flexibility to students, it may be that 2020 actual numbers are consistent with, or slightly above, projected numbers.[31]

The specific impacts to high school seniors during Spring 2020 varied by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status and this disaggregation will be an important story once the data are available. It could be, for example (and speaking entirely hypothetically) that the projected number of graduates are higher than projected, overall, but that there are fewer than projected graduates of specific populations, such as students of color – given the disparate impacts of COVID-19 and the economic disruptions. And, even those who achieved their diploma experienced a range of possible impacts on their post-high school plans for postsecondary education, work, and other parts of life. That may inevitably mean that even if these projections prove to be relatively accurate for the high school Class of 2020, they might not be as descriptive about incoming freshmen college populations.

In terms of when we might be able to compare the projected numbers to what actually occurred with the high school Class of 2020, based on WICHE’s experience with compiling the data underlying the projections, public school grade-level enrollments for school year 2019-20 are imminent, but high school graduate counts for the Class of 2020 will be available on a rolling basis state-by-state but not fully available for every state and therefore for the nation, until Fall 2021.

Class of 2021 and Future Graduate Trends Could Be Different for Many Reasons

Concurrent research and development will be needed to track and model how the pandemic is impacting education and high school graduation in the many and varied ways that cannot be easily identified by straightforward enrollment and graduate count changes—or that will take several years to emerge.

High school seniors SY 2020-21; would-be Class of 2021. In practical terms for these projections of high school graduates for the forthcoming Class of 2021, the greatest potential for the projections to be very different from the eventual actual number who graduate by spring/summer 2021 relates to how COVID-19 impacted students who were 11th graders in spring 2020 and rising seniors of school year 2020-21.

The most immediate possibility for change from projected numbers is if there was a disengagement/dropping out of students between 11th and 12th grade at different rates than historically experienced (or at least a perceived dropping out, given how it is harder to track student attendance with online learning). Even if there is no net unexpected difference in the total actual number of 11th graders progressing to 12th grade between SY 2019-20 and 2020-21, it is possible that there might be some apparent dropping out related to students transitioning to homeschooling, or transferring between public and private schools; and these types of transitions could impact the projections by sector, at least.

Current high school seniors and would-be graduates projected for the Class of 2021, might also be impacted by some more subtle and developing COVID-19 impacts. For example, their progress or plans in their senior year with intended courses may be altered (including advanced coursework such as concurrent/dual enrollment access, AP, IB etc.), and so might be extracurricular pursuits that were part of their high school completion plan (sports, music, expository activities, performances, etc.).[32] International secondary school students are likely experiencing their own unique impacts.[33] And, of course, some number of high school seniors are being impacted by lack of access to online learning technology, internet and supports, needed support for learning and other disabilities, and possibly economic and family circumstances that are further challenging their learning. Any of these or other circumstances of COVID-19 might derail some seniors from graduating in 2021. And these impacts will be occurring disparately by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.

On the other hand, there is also some evidence that the online learning environment may be beneficial for some students’ achievement.[34] And again, even if the number of graduates eventually remains somewhat similar to the number projected, only the future will tell how their post-graduation plans may have been impacted, so that the number of graduating high schoolers might not foretell incoming freshmen classes.

High school graduating classes past 2021. Beyond these considerations for the first two projected years – it could take years for COVID-19’s full impact on high school graduation to be evidenced. For example, it might be three or four years before it is evident if ninth graders transitioning in SY 2020-21 were substantially impacted by their unusual transition to high school. Similarly, initial estimates point to the possibility of greater impacts for middle schoolers, which would be evidenced around the approach to 2025.[35] And, learning loss, particularly among underserved public school students of color or low-income younger students might potentially undo some of the recent graduation improvements for these populations, over the medium and longer term.[36] Initial estimates have varied about the learning impacts of the shift to remote/online instruction, possible changes in education “quality” and high school graduation standards, and the impact of this turbulent time on learning due to pressures on children’s mental health and socioemotional states.[37]

There may be shifting of students between public, private or home schooling, which could alter the projected distribution of students and graduates by sector.[38] There will also be variations across states or in specific ways related to the recession that will involve in-depth research and utilization of other non-education data sources, such as Census and Bureau of Labor Statistics data, or research that others produce. And, over the very long term, there are some early predictions that the already ongoing birth declines may continue or be amplified.[39]

How might eventual private school trends differ from the projections? By the time of publication, the most recent data about private school students was two years lagged from public school data (private school enrollments through school year 2017-18, graduates through Class of 2017).[40] And, as discussed, the data that estimate private school populations indicates swift increases between 2013-14 and 2017-18. Thus, even barring what COVID-19 might do for the sector, the future of private school graduates is already less determinate than for public school students. (And, any changes to private school trends also implicitly affect the grand total and the public school sector, which students might be transferring between). From a projection standpoint, COVID-19 impacts may increase the existing volatility of private school trends. For example, there are some indications that families may be opting for private school amidst concern with public school re-openings or the need for the childcare.[41] And unstable private school enrollments during the Great Recession may be some indication of potential impacts to school choice of the current unique economic environment.[42]

Conclusion and Next Steps

If you discount COVID-19, the conclusions and key takeaways from these projections are relatively straightforward. Namely, improvements in high school graduation rates are leading to more high school graduates than previously projected and offsetting some – but definitely not all – of the expected national declines beginning in 2026. High school graduating classes will continue to become more diverse, led by growing proportions of Hispanic and multiracial students in particular. Our nation’s education systems must continue and redouble efforts to address systemic inequities that have resulted in disparate outcomes by race/ethnicity. It is clearly the right thing to do – and necessary for the economic success of our society – and these projections only add to the imperative by showing that a greater number of students of color will continue to flow through the education pipeline in the coming years.

But clearly, discounting COVID-19 is impossible and the pandemic adds a layer of complexity and uncertainty to these projections. WICHE provides these data for planning investments and programming in U.S. education, but acknowledges that – as always – planners and policymakers inevitably need more information for using the data given the expected limitations to their precision. This is never more true than now.

In preparing this report, WICHE has heard clearly from advisors, experts, and key stakeholders about the uncertainty introduced by the pandemic. WICHE intends to issue new information as more evidence becomes available about what might be different in the immediate or longer-term future for high school graduates due to COVID-19 and the recession.

This 10th edition is being released almost entirely online, focusing on getting the data into the hands of those who can use them and enabling transparent and efficient additions of new information as it becomes available, with an abundance of interactive charting and visualization tools.

About

WICHE provides this information free of charge in a variety of formats: reports, downloadable data, charts and profiles for state, regional and national trends, and archived presentations and forums.

To produce the projections, WICHE gathers and maintains data about the numbers of students for every grade of public and private schools for each state. projection method is a simple and frequently used cohort progression method, which observes the mathematical ratio of students in a current year compared to the number in the previous year. These ratios implicitly capture changes in the student numbers that are – for example – from migration in and out of the state, grade promotion and retention, and the impact of external environments or events on youth trends, among other things. Projections based on student counts can typically be made for 12 years out. WICHE’s projections also invoke counts of births to extend our projections out to 18 years.

In all, the 10th edition considers reported enrollments and graduates through school year 2018-19, and U.S. births, to project graduates from the Class of 2020 through 2037 for the nation, regions, and states.[43] From the available data, WICHE can produce the projections by race/ethnicity for public schools, which generate about 90 percent of U.S. graduates. Projections for private schools are state totals only, because the underlying data source does not provide the necessary detail to describe private school graduates’ race/ethnicity.

Graduates are projected through school year 2036-37 for the totals for public and private schools, and through school year 2035-36 for public school graduates by race/ethnicity. The methodology also produces grade-level enrollment projections; for this edition, enrollment projections are available for all grades through school year 2025-26, and for additional years past that for specific grades (available with the graduate projections in the downloadable datasets).

For full detail about the source data, methodology, implicit influences on the projections, and the accuracy of the projections over time, see the Technical Appendix.

Endnotes

[1] National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data, “Dropouts, Completers and Graduation Rate Reports,” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/pub_dropouts.asp. National Center for Education Statistics, “Digest of Education Statistics,” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/current_tables.asp.

[2] For example, graduation rate improvements occurred while the Great Recession and recovery occurred. This could be evidence about what might occur during this period. However, information emerging from the Fall 2020 semester suggests that past evidence might not be directly relevant, or complete, for beginning to understand the impacts of COVID-19 and this economic downturn.

[3] The U.S. total includes the 50 states and District of Columbia and covers the overwhelming majority of graduates from public high schools and the almost 10 percent of youth who attend private schools (nationally). Home-schooled or other pockets of youth are not explicitly covered by the available data. WICHE provides an estimate of the number of graduates from Bureau of Indian Education schools at the national level in this edition, but it is not included here, because it is not available for all years. Projections for Puerto Rico are also available in the detailed data, but not included here.

[4] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Natality Information: Live Births (Washington: D.C., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, accessed on November 23, 2020 at https://wonder.cdc.gov/natality.html.

[5] The predicted rates of decline for U.S. high school graduates (11 percent) are not exactly equal to the birth cohort declines (13 percent) for a number of reasons that WICHE cannot precisely quantify, but which are implicitly sensed and modeled by the projection methodology. For example, not all students begin kindergarten and first grade at the same age. And, students are promoted or repeat grades, which can diffuse changes with very young children by later years. Also, some children may be home-schooled and not be reflected in these projections. Also, immigration historically has led to somewhat more high school graduates than might be predicted by U.S. births alone; some small amount of youth in-migration might be sensed in the student enrollments that were not reflected in U.S. births (see Technical Appendix for more on this).

[6] As discussed elsewhere in this report, the trends described by a focus on single-race non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native identity provide a contrary picture to the population increases that are occurring with a broader definition of individuals with any American Indian/Alaska Native identity.

[7] Births in the categories Asian or Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, separately, or multi-racial, are not available until 2016. Therefore, WICHE does not produce the extended projections for these series, because the data are available for too few years.

[8] Projections are also provided in the detailed data for the nine Census regional subdivisions. (See also Census Regions and Divisions of the U.S. map at https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf).

[9] Scott Jaschik, “Are Prospective Students About to Disappear?” Inside Higher Ed, January 8, 2018, accessed on December 3, 2020, at https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2018/01/08/new-book-argues-most-colleges-are-about-face-significant-decline. Megan Adams and Samantha Smith, “The demographic cliff is already here – and it’s about to get worse,” Education Advisory Board, May 28, 2020), accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://eab.com/insights/expert-insight/enrollment/the-demographic-cliff-is-already-here-and-its-about-to-get-worse/.

[10] Graduates from Puerto Rico contributed roughly 22,000 Hispanic public high school graduates in the Class of 2019 (about 0.65 percent of the combined total of Hispanic public high school from the 50 states, District of Columbia and Puerto Rico). Based on Puerto Rico public school enrollments for school year 2018-19, by the Class of 2030 there could be fewer than 10,000 public high school graduates from Puerto Rico.

[11] Due to limitations with the births data used to project the outer years, WICHE is only able to separately project Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander graduates through the Class of 2030. Also, each series is independently projected so the separate projections may not equal when summed.

[12] Similar to the separate Asian and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander series, it is not possible to project this category beyond the Class of 2030. However, were the number of these graduates not at least estimated for 2031 to 2036, the sum of the public high school graduates by race/ethnicity would be noticeably incomplete compared to the public school graduate total. Therefore, for the Class of 2031 to 2036, multiracial public high school graduates are estimated based on continuing the share they represent of non-Hispanic graduates by the Class of 2030.

[13] United States Census Bureau, “2019 Population Estimates by Age, Sex, Race and Hispanic Origin,” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html.

[14] United States Census Bureau, “Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States, April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019,” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html. WICHE computations and analysis.

[15] United States Census Bureau, 2018 American Community 1-Year Estimates, Survey Public Use Microdata, (Suitland, MD: United States Census Bureau). Data available at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/microdata.html. WICHE computations and analysis.

[16] United States Department of the Interior, “Bureau of Indian Education: Schools,” accessed on November 24, 2020 at https://www.bie.edu/schools/directory.

[17] Aiden Woods, “The Federal Government Gives Native Students an Inadequate Education, and Gets Away With It,” ProPublica, August 6, 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.propublica.org/article/the-federal-government-gives-native-students-an-inadequate-education-and-gets-away-with-it.

[18] National Center for Education Statistics, “CCD Data Files,” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/files.asp.

[19] National Center for Education Statistics, “Private School Universe Survey (PSS),” accessed on November 23, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/files.asp#Page:1. William J. Hussar and Tabitha M. Bailey, Projections of Education Statistics to 2024, (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, September 2016), accessed on November 23, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubs2016/2016013.pdf.

[20] Stephanie Ewert, The Decline in Private School Enrollment, (Suitland, MD: United State Census Bureau: Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division, January 2013), accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2013/acs/2013_Ewert_01.pdf.

[21] But, for example, one source of enrollment growth for private schools was international students (including those seeking U.S. high school diplomas), and that appears to have recently declined, according to Institute of International Education. See Leah Mason and Natalya Andrejko, Studying for the Future: International Secondary Students in the United States, (New York, NY: Institute of International Education, 2020), accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://iie.widen.net/s/r2trwgnvbq.

[22] Bill Hussar, Jijun Zhang, Sarah Hein, Ke Wang, Ashley Roberts, Jiashan Cui, Mary Smith, Farrah Bullock Mann, Amy Barmer, and Rita Dilig, The Condition of Education 2020, (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2020), accessed December 8, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020144.pdf . (Specifically, Private School Enrollment section and tables.)

[23] Hussar and Bailey, 2016.

[24] Hussar et al, 2020. See, for example, “Public High School Graduation Rates” section.

[25] The term “on-time graduation rate” refers to the methodology states are required to use to report graduation rates to the U.S. Department of Education, which is an adjusted cohort graduation rate (ACGR) method. For more information see National Center for Education Statistics, “High school graduation rates,” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=805.

[26] National Center for Education Statistics, “Digest of Education Statistics: Table 219.46, Public high school 4-year adjusted cohort graduation rate (ACGR), by selected student characteristics and state: 2010-11 through 2017-18,” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19_219.46.asp.

[27] Because the WICHE projections encompass total annual public high school graduates, not just those considered graduating ‘on-time’ within four years of ninth grade, the data underlying these projections will be slightly higher even than suggested by on-time graduate estimates. By WICHE’s estimate, nationally, there are about 6 percent more annual total public high school graduates than the number of who graduate on-time.

[28] Representation of U.S. overall public school ACGR rates between 2013-14 and 2017-18 (the latest year available), using the five-year weighted average approach employed by the projections.

[29] Kunwon Ahn, Jun Yeong Lee, John V. Winters, “Employment Opportunities and High School Completion during the COVID-19 Recession,” Economics Working Papers: Department of Economics, Iowa State University, October 19, 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1114&context=econ_workingpapers.

[30] Megan Brenan, “K-12 Parents’ Satisfaction With Child’s Education Slips,” Gallup, August 25, 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://news.gallup.com/poll/317852/parents-satisfaction-child-education-slips.aspx.

[31] Education Week, “Data: How is Coronavirus Changing States’ Graduation Requirements?” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.edweek.org/ew/section/multimedia/data-how-is-coronavirus-changing-states-graduation-requirements.html.

[32] Greg Toppo, “Sign on, Zoom in, Drop Out: Pandemic Sparks Fears that Without Sports and Other Activities, Students Will Disengage from School,” The 74 Million, November 12, 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.the74million.org/article/sign-on-zoom-in-drop-out-pandemic-sparks-fears-that-without-sports-and-other-activities-students-will-disengage-from-school/.

[33] Mason and Andrejko, 2020.

[34] Nora Fleming, “Why Are Some Kids Thriving During Remote Learning?” Edutopia, April 24, 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.edutopia.org/article/why-are-some-kids-thriving-during-remote-learning. Erika Christakis, “School Wasn’t So Great Before COVID, Either,” The Atlantic, December 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/12/school-wasnt-so-great-before-covid-either/616923/.

[35] Lucrecia Santibanez and Cassandra Guarino, “The Effects of Absenteeism on Cognitive and Social-Emotional Outcomes: Lessons for COVID-19,” EdWorkingPapers, 20:261 (2020), accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.edworkingpapers.com/ai20-261.

[36] Megan Kuhfield, James Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek and Jing Lui, “Projecting the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievements,” EdWorkingPapers, 20:226 (2020), accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.edworkingpapers.com/ai20-226. Marta W. Aldrich, “’COVID slide’: Struggling Tennessee students have fallen even further behind, say superintendents,” Chalkbeat, September 22, 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://tn.chalkbeat.org/2020/9/22/21451931/covid-slide-struggling-tennessee-students-have-fallen-even-further-behind-say-superintendents. C. Kirabo Jackson, Cora Wigger and Heyu Xiong. “The Costs of Cutting School Spending,” Education Next, Vol. 20, No. 4 (2020), accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.educationnext.org/costs-cutting-school-spending-lessons-from-great-recession/.

[37] Megan Kuhfield, James Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek and Karyn Lewis. Learning during COVID-19: Initial findings on students’ reading and math achievement and growth, (Portland, OR: NWEA, Collaborative for Student Growth, November 2020), accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.nwea.org/content/uploads/2020/11/Collaborative-brief-Learning-during-COVID-19.NOV2020.pdf. Ember Smith and Richard V. Reeves, “Students of color most likely to be learning online: Districts must work even harder on race equity,” Brookings, September 23, 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/how-we-rise/2020/09/23/students-of-color-most-likely-to-be-learning-online-districts-must-work-even-harder-on-race-equity/. Center for Promise, “What Drives Learning: Young People’s Perspectives on the Importance of Relationships, Belonging, & Agency,” America’s Promise Alliance, September 23, 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.americaspromise.org/resource/what-drives-learning-young-peoples-perspectives-importance-relationships-belonging-agency.

[38] Brenan, 2020.

[39] Melissa S. Kearney and Philip B. Levine, Philip B, “Half a million fewer children? The coming COVID baby bust,” Brookings, June 15, 2020, accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://www.brookings.edu/research/half-a-million-fewer-children-the-coming-covid-baby-bust/.

[40] Data from the Private School Universe Survey for the 2019-20 school year and 2018-19 high school graduates are estimated to be released in Spring to Summer 2021 (per conversation with the NCES program coordinator).

[41] Brenan, 2020.

[42] Ewert, 2013

[43] Data were not available at the time of publication to provide projections for the U.S. territories and freely associated states that are affiliated with the WICHE region (including Guam and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands).